And It Comes to an End

Emptiness. That's all I feel. We're in the very Spanish, very modern, very sanitary funeral home. In a refrigerated room behind plate glass, lies my father in his casket, on view. Flowers surround him. People start to come in. They come to me, the principle mourner, give me the mandatory kiss on each cheek, murmur platitudes. The hour of the funeral is approaching. Until now, it has seemed simply like a strange day, spending our time in a largish room with chairs and couches along the walls, talking with friends about all sorts of matters, trying to bring about world peace and end hunger everywhere, as if we could do so just by voicing our opinions. Now, the worst moment looms before me, worse even than when my father stopped breathing in his hospital room.

The priest comes in. We all rise. I don't listen. I move my mouth as if I'm repeating the Lord's Prayer with the rest. The difficult moment is upon us. Everyone begins to leave. We wait to leave behind the hearse.

It pulls out and we pull out behind it. It's a short drive to the church and its cemetery. We go slowly. When we arrive, we park in the spot reserved for the family and wait for the coffin to be carried into the church. We follow behind, my head bowed because I don't want to make eye contact with anyone. We enter through the rear door, and walk all the way to the front, where we sit behind the coffin. I do not look around. I don't want to see anyone.

Three priests come out. The fat one presides and says the Mass. The other two assist in the absence of altar boys. A woman with an electric organ plays and sings hymns. We stand, we sit, we kneel, we stand again. I don't even bother to move my mouth in the responses now, and pretend to cross myself at the appropriate moments. As the Mass draws to a close, I dread the coming moments.

The pall bearers arrive as the last hymn is being sung. They lift the coffin and begin to walk up the aisle, the priest behind. We step into the aisle and follow, my husband and I holding hands. I look down, not wanting to see anyone, studying the pattern in the runner laid down on the stone floor. I feel the eyes on me, everyone standing at the benches, as we continue to the rear door. My introverted self recoils from them. Once outside, we turn left, to go around the church to the end of the cemetery, where the niche has been prepared. I keep looking down, away from everyone. My lip twitches up, and I breathe deeply.

We put my father to rest with my mother. It seems appropriate, after having spent most of their lives together. I feel like crying, I feel like breaking something, I feel like starting to run away and not stopping until my lungs and legs give out. When we arrive home, I don't know what to feel. I wish he had shown his love. I wish he had told me, at least once in my adult life, that he loved me.

My husband says it's because he had a very difficult life. I don't know. Others who went through similar experiences have been more open about their emotions. And others were just like him, too. He was born poor, out of wedlock to a mother who already had a daughter thirteen years older than him. He had to start working early to help support the family. At nine years, he was already carrying picks for the stone masons he was apprenticed to, leaving the house before daybreak, walking miles into the hills to break stones, and learn to fashion them. He would take a piece of bread for lunch, and drink water from a brook.

He spent most of his adolescence like that, except for a few months when he was ill and bedridden. Those months were when a priest came and taught him to read and write. He fashioned stone into monuments. Some of the stone pillars that decorate the niches in many cemeteries in the surrounding parishes were chiseled by my father. He continued with the tradition that created the churches and cathedrals that stand as monuments to man's faith in the eternal. But after he married, he was offered an opportunity to work on a merchant ship. He took advantage of that opportunity and spent a couple of years travelling the world. He visited Bombay, London, Valencia, Sevilla, Rotterdam, London, and Norfolk, Virginia. It was at Norfolk, after a heavy discussion with the first mate of the ship, that he went ashore, called his brother-in-law in Boston, and took the train north, abandoning the seas and becoming an illegal immigrant.

In Boston, my uncle found him a job in construction with a small, family-run company. The brothers who ran it were Italian and had other Italian workers. Between Italian and Spanish, my father and his employers communicated. At the same time, a little English went into my father; enough to be able to survive there for almost a year. He was detained and sent back to Spain. There, he continued working with stone.

When I was born, my parents had been doing the paperwork to legally emigrate to Boston, with the sponsorship of my uncle, by then an American citizen. I was then included in the paperwork and was issued my green card, as well. The card was literally green, with our picture affixed under plastic. My father gave his up when he became a U.S. citizen in the mid seventies. I remember helping him study, because he couldn't read English. The day of the citizenship exam, he was so nervous, he was allowed to go outside the building, and in my uncle's presence, write down answers to the exam. He was approved, though, and swore allegiance to the flag.

Through ups and downs, we spent twenty-two years in Boston. Then, my father was diagnosed with stomach cancer in 1990. It was caught in time, and he didn't even need any follow-up therapy of any kind. We moved back to Spain, where he finished jobs around the house, such as finishing the barn, which had spent twenty-two years half-built. It's of stone, and in the early years of his retirement, my father reverted to what he had best worked at. He found the stone, and with clay, put it together to finish what he had started.

After my mother died, twelve years ago, my father stopped going out. He would sometimes go to funerals or anniversary Masses with a neighbor. Very occasionally, he would go to eat at his nephew's house, where he had been born and raised. More often, he had been going to doctors' appointments until now. And now that is done.

Miguel Romero Perez, 1931 - 2017.

The priest comes in. We all rise. I don't listen. I move my mouth as if I'm repeating the Lord's Prayer with the rest. The difficult moment is upon us. Everyone begins to leave. We wait to leave behind the hearse.

It pulls out and we pull out behind it. It's a short drive to the church and its cemetery. We go slowly. When we arrive, we park in the spot reserved for the family and wait for the coffin to be carried into the church. We follow behind, my head bowed because I don't want to make eye contact with anyone. We enter through the rear door, and walk all the way to the front, where we sit behind the coffin. I do not look around. I don't want to see anyone.

Three priests come out. The fat one presides and says the Mass. The other two assist in the absence of altar boys. A woman with an electric organ plays and sings hymns. We stand, we sit, we kneel, we stand again. I don't even bother to move my mouth in the responses now, and pretend to cross myself at the appropriate moments. As the Mass draws to a close, I dread the coming moments.

The pall bearers arrive as the last hymn is being sung. They lift the coffin and begin to walk up the aisle, the priest behind. We step into the aisle and follow, my husband and I holding hands. I look down, not wanting to see anyone, studying the pattern in the runner laid down on the stone floor. I feel the eyes on me, everyone standing at the benches, as we continue to the rear door. My introverted self recoils from them. Once outside, we turn left, to go around the church to the end of the cemetery, where the niche has been prepared. I keep looking down, away from everyone. My lip twitches up, and I breathe deeply.

We put my father to rest with my mother. It seems appropriate, after having spent most of their lives together. I feel like crying, I feel like breaking something, I feel like starting to run away and not stopping until my lungs and legs give out. When we arrive home, I don't know what to feel. I wish he had shown his love. I wish he had told me, at least once in my adult life, that he loved me.

My husband says it's because he had a very difficult life. I don't know. Others who went through similar experiences have been more open about their emotions. And others were just like him, too. He was born poor, out of wedlock to a mother who already had a daughter thirteen years older than him. He had to start working early to help support the family. At nine years, he was already carrying picks for the stone masons he was apprenticed to, leaving the house before daybreak, walking miles into the hills to break stones, and learn to fashion them. He would take a piece of bread for lunch, and drink water from a brook.

He spent most of his adolescence like that, except for a few months when he was ill and bedridden. Those months were when a priest came and taught him to read and write. He fashioned stone into monuments. Some of the stone pillars that decorate the niches in many cemeteries in the surrounding parishes were chiseled by my father. He continued with the tradition that created the churches and cathedrals that stand as monuments to man's faith in the eternal. But after he married, he was offered an opportunity to work on a merchant ship. He took advantage of that opportunity and spent a couple of years travelling the world. He visited Bombay, London, Valencia, Sevilla, Rotterdam, London, and Norfolk, Virginia. It was at Norfolk, after a heavy discussion with the first mate of the ship, that he went ashore, called his brother-in-law in Boston, and took the train north, abandoning the seas and becoming an illegal immigrant.

In Boston, my uncle found him a job in construction with a small, family-run company. The brothers who ran it were Italian and had other Italian workers. Between Italian and Spanish, my father and his employers communicated. At the same time, a little English went into my father; enough to be able to survive there for almost a year. He was detained and sent back to Spain. There, he continued working with stone.

When I was born, my parents had been doing the paperwork to legally emigrate to Boston, with the sponsorship of my uncle, by then an American citizen. I was then included in the paperwork and was issued my green card, as well. The card was literally green, with our picture affixed under plastic. My father gave his up when he became a U.S. citizen in the mid seventies. I remember helping him study, because he couldn't read English. The day of the citizenship exam, he was so nervous, he was allowed to go outside the building, and in my uncle's presence, write down answers to the exam. He was approved, though, and swore allegiance to the flag.

Through ups and downs, we spent twenty-two years in Boston. Then, my father was diagnosed with stomach cancer in 1990. It was caught in time, and he didn't even need any follow-up therapy of any kind. We moved back to Spain, where he finished jobs around the house, such as finishing the barn, which had spent twenty-two years half-built. It's of stone, and in the early years of his retirement, my father reverted to what he had best worked at. He found the stone, and with clay, put it together to finish what he had started.

After my mother died, twelve years ago, my father stopped going out. He would sometimes go to funerals or anniversary Masses with a neighbor. Very occasionally, he would go to eat at his nephew's house, where he had been born and raised. More often, he had been going to doctors' appointments until now. And now that is done.

Miguel Romero Perez, 1931 - 2017.

|

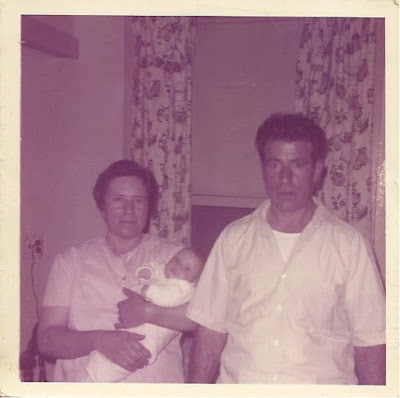

| May, 1969, just after arriving in Boston. My parents and me. |

One cannot comment on content of such a personal blog other than to say thank you for sharing. The saddest part of a death, is the past is now sealed, no more hope for a change of attitude, a chance to add a sentence. We live with it. We deal with it. And whatever we feel is valid.

ReplyDelete