History is Also Ours

Women have always been sidelined in history. History has always been made by men. Theirs are the names in the books to remember. Robespierre, Danton, and Marat are the men associated with the French Revolution, but the beginning of the end was when Louis XVI and his family was brought from Versailles to the Louvre by thousands of Parisian women who wanted them to see for themselves the poverty those in the city suffered. Did these women act under a banner of idealism? No, they acted under the pragmatist banner of the price of bread.

Men have always accused women of acting romantically and unrealistically. We have always been accused of being dreamers. Yet, the dreamers in history have generally been men. Yes, there have been women who have influenced thought through their writings rather than through their actions, such as Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, Mary Wollstonecraft, or even the notorious Ayn Rand. But when uprisings begin over the basics of life, they tend to be led, or majorly participated in, by women.

The Bread and Roses Strike in 1912, in Lawrence, Massachusetts was one such uprising. Women in the textile industry arose in protest that, along with the reduction in their work week to 54 hours (applauded), came a reduction in pay (not applauded). After two months, in which most children were sent to families elsewhere so they wouldn't suffer starvation, and three deaths (1 woman, 2 men, all immigrants), the mills capitulated. Unfortunately, after a few years, the companies chipped away at the pay raise given, and conditions returned to what they had been.

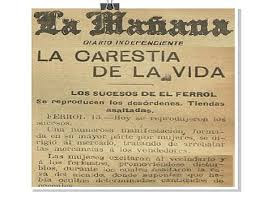

In Spain, women have also been at the head of a few revolts. One happened a hundred and one years ago, in March, 1918, in Sedes, a small township next to Ferrol. World War I was still raging in Europe, but Spain was neutral. The rest of Europe could barely feed its people thanks to the battlefields, so large Spanish farms took advantage of the prices and sold most grain abroad, leaving a small quantity to sell at home. That created shortages and increase in prices. It got to the point where a day's earnings were barely enough to buy a dozen eggs. Flour and bread, the mainstay of the poor, were becoming prohibitive. Women who found themselves unable to buy flour decided to go together as a group to complain to the mayor of Xubia, another nearby town. The mayor wouldn't agree to see them, so they went to talk with some of the merchants who were hoarding basic necessities while prices went up. The merchants had their guards shoot at them, and the women retaliated by throwing stones. That was the beginning of a bloody week.

Aside from the price of basic foods, the peasants were angry that their taxes were much higher than those of the hoarding merchants. The workers at Ferrol's shipyards were conscious of the proletarian uprisings in Russia, and wanted to better their lot. The women who worked at the textile plant in Xubia were angry about their pittance salaries, the long hours, and the dangerous conditions under which they worked. The field was ripe for the week long uprising led, mostly, by women.

Strikes and protests were organized by the women. The first to organize were the women at the textile factory in Xubia. On the 10th, in Ferrol, shots were fired against protestors, killing a 12 year old boy and a 16 year old worker from the Navy yard. On the 13th, at the market fair in Sedes, a protest was led to the mayor's house. The Guardia Civil shot at the protestors, killing at least seven and wounding many others. The next day, six thousand people walked from Ferrol to Sedes, to attend the funeral. On the 15th, a general strike was declared in Ferrol, and the military was sent in.

Women generally led the disturbances. They cut off the railway to Ferrol, carts carrying milk and other foods away to be sold were sacked, businesses and stores were forced to close. Bullets were responded to with stones.

In the end, the uprising was quelled, but things changed. The mayors of some of the affected towns resigned. Prices were forced down and hoarding discouraged. The government granted amnesty in April to those involved, except those incarcerated, who had to serve the time imposed. The role of women had been noted. The newly formed Galician nationalist movement called for the equality of rights for men and women, the first time it was called for in Spain.

A statue was erected to those who died in Sedes in 1933, with money collected from neighbors, but it was demolished by the fascist son of one of the hoarders against whom so many marched. To celebrate the anniversary, another one was erected last year. Our voices will not be silenced, neither by time nor by men.

Men have always accused women of acting romantically and unrealistically. We have always been accused of being dreamers. Yet, the dreamers in history have generally been men. Yes, there have been women who have influenced thought through their writings rather than through their actions, such as Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, Mary Wollstonecraft, or even the notorious Ayn Rand. But when uprisings begin over the basics of life, they tend to be led, or majorly participated in, by women.

The Bread and Roses Strike in 1912, in Lawrence, Massachusetts was one such uprising. Women in the textile industry arose in protest that, along with the reduction in their work week to 54 hours (applauded), came a reduction in pay (not applauded). After two months, in which most children were sent to families elsewhere so they wouldn't suffer starvation, and three deaths (1 woman, 2 men, all immigrants), the mills capitulated. Unfortunately, after a few years, the companies chipped away at the pay raise given, and conditions returned to what they had been.

In Spain, women have also been at the head of a few revolts. One happened a hundred and one years ago, in March, 1918, in Sedes, a small township next to Ferrol. World War I was still raging in Europe, but Spain was neutral. The rest of Europe could barely feed its people thanks to the battlefields, so large Spanish farms took advantage of the prices and sold most grain abroad, leaving a small quantity to sell at home. That created shortages and increase in prices. It got to the point where a day's earnings were barely enough to buy a dozen eggs. Flour and bread, the mainstay of the poor, were becoming prohibitive. Women who found themselves unable to buy flour decided to go together as a group to complain to the mayor of Xubia, another nearby town. The mayor wouldn't agree to see them, so they went to talk with some of the merchants who were hoarding basic necessities while prices went up. The merchants had their guards shoot at them, and the women retaliated by throwing stones. That was the beginning of a bloody week.

Aside from the price of basic foods, the peasants were angry that their taxes were much higher than those of the hoarding merchants. The workers at Ferrol's shipyards were conscious of the proletarian uprisings in Russia, and wanted to better their lot. The women who worked at the textile plant in Xubia were angry about their pittance salaries, the long hours, and the dangerous conditions under which they worked. The field was ripe for the week long uprising led, mostly, by women.

Strikes and protests were organized by the women. The first to organize were the women at the textile factory in Xubia. On the 10th, in Ferrol, shots were fired against protestors, killing a 12 year old boy and a 16 year old worker from the Navy yard. On the 13th, at the market fair in Sedes, a protest was led to the mayor's house. The Guardia Civil shot at the protestors, killing at least seven and wounding many others. The next day, six thousand people walked from Ferrol to Sedes, to attend the funeral. On the 15th, a general strike was declared in Ferrol, and the military was sent in.

Women generally led the disturbances. They cut off the railway to Ferrol, carts carrying milk and other foods away to be sold were sacked, businesses and stores were forced to close. Bullets were responded to with stones.

In the end, the uprising was quelled, but things changed. The mayors of some of the affected towns resigned. Prices were forced down and hoarding discouraged. The government granted amnesty in April to those involved, except those incarcerated, who had to serve the time imposed. The role of women had been noted. The newly formed Galician nationalist movement called for the equality of rights for men and women, the first time it was called for in Spain.

A statue was erected to those who died in Sedes in 1933, with money collected from neighbors, but it was demolished by the fascist son of one of the hoarders against whom so many marched. To celebrate the anniversary, another one was erected last year. Our voices will not be silenced, neither by time nor by men.

Comments

Post a Comment